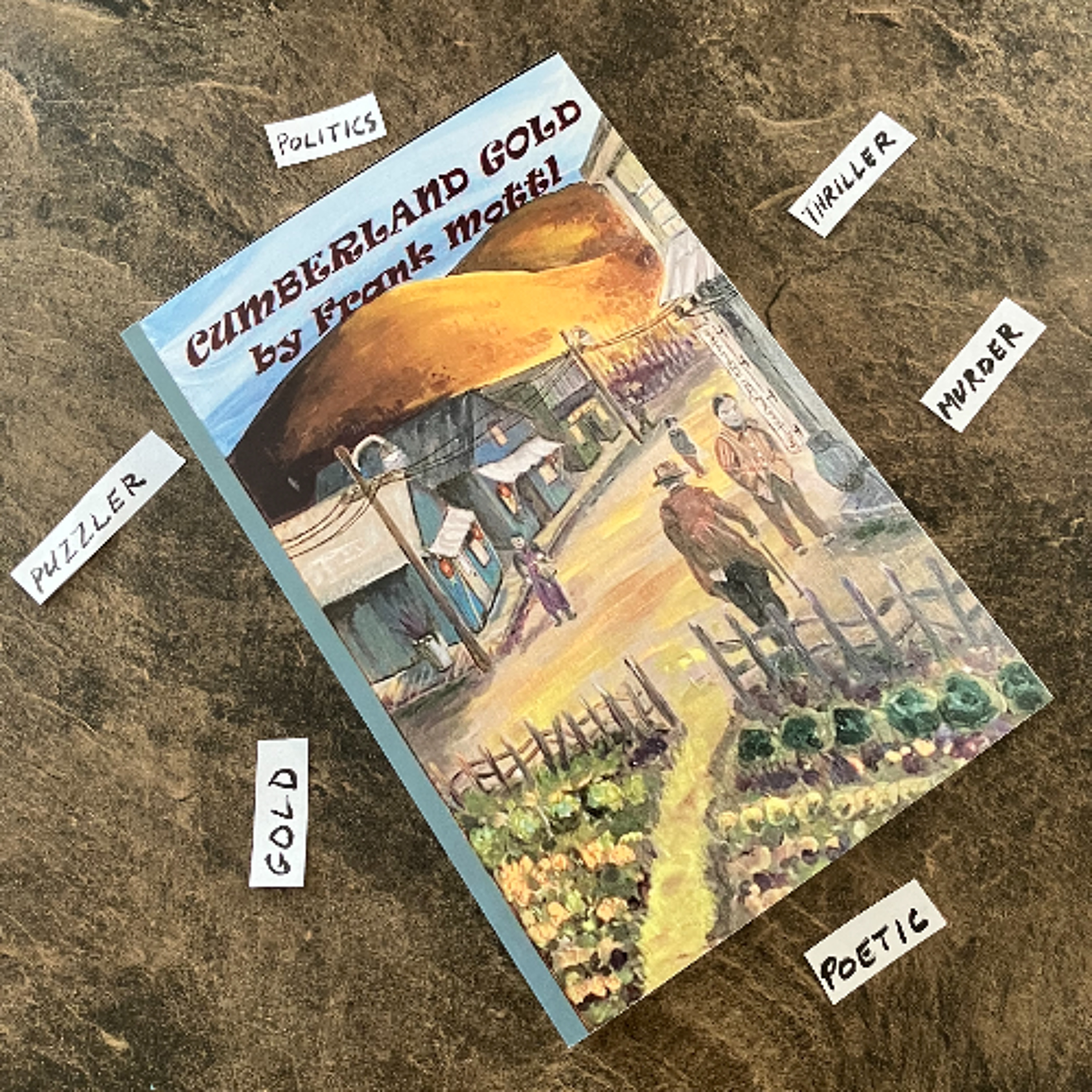

Cumberland Gold for Frank Mottl

- Author

- roy.hales9.gmail.com

- Published

- Mon 17 Feb 2025

- Episode Link

- https://soundcloud.com/the-ecoreport/cumberland-gold-for-frank

Roy L Hales/Cortes Currents - Frank Mottl’s latest novel, Cumberland Gold, takes us to the quaint village of Cumberland BC. This is the same setting as his first novel, The Cumberland Tales, in which Mottl described the community he knew in the 1960s. Only now he is writing about the late 19th century, when Lord Dunsmuir (1825-89) was attempting to recruit Chinese immigrants to work in his coal mine.

Mottle explained, “ I did some research at the Cumberland Museum, and there was an unsolved homicide in the 19th century in the old Cumberland Chinatown. Nobody knew much about it, other than it was unsolved. That really appealed to me, so I just ran with it. Of course I spent a year teaching in China, so it did have a lot of that Chinese influence inside of it.”

Cortes Currents: I'm wondering about the divisions you mentioned in the Chinese community, with the secretive Buddhist and Taoist basement temples and the Confucian temple and the Presbyterian church. You're tracing them back to the periodic persecutions of Chinese academia during the early Qing dynasty.

Frank Mottl: “Yes, there were a lot of revenge scenarios in ancient China, and I portray some of that in the book. What I did is I pulled those old revenges into the Cumberland Chinatown to give it a political edge, to make more sense of what was going on. So I introduced the Qing dynasty (1644-1912), the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), and the Tang dynasty (618-907). Each dynasty had their loyalists and there were betrayals. Especially between the Ming and the Qing dynasties. There's one passage in the book about a Ming dynasty general actually leaving the capital’s gate open so Qing forces could come in and start slaughtering people.”

Cortes Currents: Was that kind of division actually occurring among the Chinese communities in British Columbia and San Francisco?

Frank Mottl: “As far as I know, no - but can I say for sure? A lot of people hold on to political beliefs, so it would not surprise me if the old Chinatown held on to these things.”

Cortes Currents: I like that scene where Dougal learned how to speak Cantonese. Do you want to talk a little bit more about that one?

Frank Mottl: “That’s from a true scenario. My wife told it to me. One of her relatives did a speech in front of a group of people, I'm not sure if it was in his native Norwegian. He assumed that the people could understand him, then all of a sudden realized that nobody knew what the heck he was saying.”

“As soon as I heard that story I thought 'oh my god this is great' because of course in China, a Mandarin speaker can't understand a Cantonese speaker. They are two different dialects. I thought that would be great because it was a real nice little conflict where the bad guy is embarrassed In front of this big union hall meeting with all of these Chinese gentlemen watching him and they don't understand what he's saying. His higher up, Lord Dunsmuir, had no clue. He said, ‘Wow, wow, it's really going great.’”

Cortes Currents: I noticed that you brought one of the characters over from the Cumberland Tales, Sam Yick. Mind you, it could have been his grandfather. Do you want to tell us a little about this?

Frank Mottl: “The character intrigues me and I wanted to get some poetry in there. I knew that I would, I wanted to have two characters that were poets. There's an old Japanese technique from the 14th century where they would make the characters poets. So I stuck with Sam Yick and then I came up with this other character's name called Crowheart.”